These two episodes mark a major change in the story telling. No combats, no opponents, no threats of any kind, but instead we are treated to some internal and external dialogue which demonstrate how little humans have changed over the past 800 years.

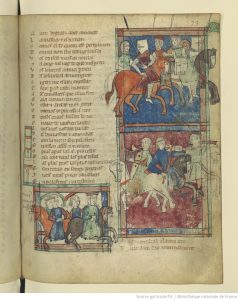

Jaufre is on his way back to see Brunissen, because that’s where he’s left his heart (as he says), but on the way he’s returning Augier’s daughter to her family home. Augier sees him coming, together with a veiled maiden, and recognises him immediately – but oddly, fails to recognise his own daughter. Perhaps it’s a question of context, as Augier is convinced that the worst has happened after his daughter was abducted by the giant. Despite his bereavement, when he sees Jaufre he dismounts and goes running up to meet him, jumping for joy. Perhaps this is why Jaufre mischievously and wilfully suggests that this maiden will be a perfectly suitable replacement for his lost daughter, but doesn’t maintain the painful joke for too long.

In these two episodes there are a few moments when Jaufre (and indeed Brunissen) say things aloud which are the opposite of what they’re thinking. The narrator lets us know their thoughts, and the result is that there is some humour involved but also a glimpse behind the courtly behaviour and good manners. Augier’s daughter (who is never named) has worked out that although she may be Jaufre’s “maiden” to whom he owes service, she is not the one he loves, and she reproaches her father for his rather heavy-handed attempts at getting Jaufre to stay. How many parents have told their children that you shouldn’t ask for what you know you can’t have? (We hear the opposite of this later on, when Brunissen says that you should always reach out for what you want!) Meanwhile Augier does try to persuade Jaufre that Brunissen has never loved anyone. This isn’t likely to change Jaufre’s mind or put him off, but it gives him something to think about.

On, then, to Monbrun, but on the way they encounter the hapless seneschal who has been looking for Jaufre the whole time, under instructions from Brunissen. Again, Jaufre plays a little game, pretending to be reluctant to go with the seneschal in case Brunissen repeats her autocratic behaviour from last time and has him imprisoned and beaten. The seneschal has to explain what of course Jaufre already knows about the great lamentation, and also gives us the surprising comparison that Brunissen would be happier to see him than “a vision of Jesus”. This comes after Jaufre has compared the beatings he received to the treatment given to Christ on the cross, and these references (there will be more) suggest that after Jaufre’s battle with the demon in the forest and victory over Taulat he has become a saviour-figure.

Brunissen is of course impatient and irascible, but eventually orders a superb welcome for the returning hero, and then we see the reunion. It’s realistic and heart-warming. They can’t speak to each other in the great crowd of people without shouting. They both long to be somewhere quiet together, but that’s not possible. It’s all happening in the public eye, and neither of them is quite sure what they should say to each other even if it were possible. Meanwhile the seneschal manages to fill Jaufre in with a more complete account of what had taken place on his visit – and we have the relatively rare event of a hero admitting that he had in fact been scared. The narrator refers to the Ovidian doctrine of Love’s arrow, and the illness of Love. It’s worth noting that not all of this is poetic metaphor – some scholars have concluded that at this period of history love was considered a condition which could indeed cause fever and many other symptoms, and could even lead to death. Luckily that’s not going to happen to our two lovers, who just have to straighten out what they’re going to say to each other. My adaptation of the story has shortened some of the internal dialogues, but I wanted to keep the poetic flavour of the writing as best I could. The original creator of “Jaufre” was obviously familiar with and referred to a number of troubadour poems, while keeping within the octosyllabic rhyming couplets, and so although some of my lines will seem somewhat clichéd and clunky the concepts were not as over-used then as they may be today. However, what is also obvious is that these two young lovers are indulging in exactly the same over-thinking process as lovers today – one of my favourite moments is when Jaufre considers the flower Brunissen has given him. There is also the gentle humour of Jaufre being so brave in combat but utterly tongue-tied when it comes to talking about his feelings, while Brunissen is the one who can speak up and manoeuvre the conversation the way she wants it to go. Just as it seems that Jaufre will never say what he thinks, he comes up with a most lyrical and beautiful declaration of his love. In my recording, David Yardley’s setting of these words underpins most of the rest of their dialogue, and for those interested in the original Occitan, here it is:

Vos est cella c’ai encobida

Vos est ma mortz, vos est ma vida

Vos est cella que a deslìure

Mi podes far morir o vìure

Vos est cella que senz engan

Am et cre et tem et reclam

Vos est mus gaugs, mos alegrierz

Et vos est tuz muns consiriers

Vos est mon delietz, mun consolatz

Per vos ai gaug can sui iratz

Vos est cela que-m pot valer

Et que-m pot, si-s vol, decaser

Vos est cela per cui mi clam

Vos est cela per cui aflam

Vos est cela de cui mi lau

Vos est cela qui ten la clau

De tot mon ben, de tot mon mal

Vos est cela si Dieus me sal

Que-m pot far volpil o ardit

Si-s vol, o pec o exernit.

My English version starts a little earlier in Jaufre’s speech, but says

“My lady, there has never been a wise man or a fool

Who has spoken out more honestly, so please do not be cruel

I can no longer hide my love – you are my life and death

You have the power to make me live or take my final breath.

You are the one I love, without pretence, with no deceit

My heart is full of trust and joy, and love in each heart beat

You are my joy and happiness, my hope and comfort too

All my courage and my bravery now will be inspired by you

One word from you can make me sad or make my spirit soar

Love for you has changed me from the fool I was before.”

Brunissen of course has to bring this back down to earth. Many men have declared their love but very few can be trusted. Poetry, in other words, is all very well, but she’s looking for real commitment. She’s looking for marriage, and a marriage celebrated before King Arthur. Luckily, Jaufre is more than ready for this, while also wanting to make it clear that he’s not a fortune hunter.

The mixture of poetry, lyricism, standard formulae regarding love and then pragmatism is a fascinating blend. This is almost, but not quite, a fairy tale in which the brave prince wins the hand of the princess, but although the princess is in love she is fully aware of the practicalities and the realities of court gossip. Jaufre, it seems, will agree to anything as long as Brunissen loves him. Brunissen is a very astute young woman and insists on getting things done properly.

How realistic is this, historically? Not very. Marriages between young people within the nobility were arranged for dynastic and property reasons, not love. There are some stories of arranged marriages where love developed between the couples, and (to return to my hypothesis about the creation of “Jaufre”) Leonor’s parents (Eleanor of England and Alfonso VIII of Castile) seem to have been genuinely and enduringly fond of each other. “Jaufre” is, however, a work of imagination. It is possible that Brunissen is intended to depict Leonor, while Jaufre may be modelled on James I of Aragon, but it is unlikely that their marriage had much love within it. There could also be references to Alienor of Aquitaine and Henry II of England, whose marriage initially did appear to show signs of strong physical attraction at least. However, while it may not have been a realistic depiction of 13th century marriages, it is also not what many people assume to be “courtly love”. This is a relationship in which Brunissen insists fidelity is a key feature. It’s love of the mind and heart, but there’s a physical component to it – she wants to be in his arms just as much as he wants to hold her. The idea of this marriage is fairly close to what we would want today. (If you are interested in this, I have written about it in far more detail in my PhD thesis, which is available via the university ORCA system, and I can supply full references if you contact me.)