1 The Tale of Jaufre is a relatively little-known story. There are also a number of unresolvable questions about how it came to be created, and why. The facts that can be ascertained are that it was written for a king of Aragon, that it was written in Occitan, and that it survives in two complete manuscripts (now in the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris) which date from the late 13th century. These manuscripts appear to be based on two different originals, and are later copies as they contain some scribal errors, so the first telling of Jaufre must have been earlier, in order to generate at least two versions and then the manuscripts. We will never know at what point it was first written down, or whether the creator of the story actually made a physical, written version.

The Tale of Jaufre is a relatively little-known story. There are also a number of unresolvable questions about how it came to be created, and why. The facts that can be ascertained are that it was written for a king of Aragon, that it was written in Occitan, and that it survives in two complete manuscripts (now in the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris) which date from the late 13th century. These manuscripts appear to be based on two different originals, and are later copies as they contain some scribal errors, so the first telling of Jaufre must have been earlier, in order to generate at least two versions and then the manuscripts. We will never know at what point it was first written down, or whether the creator of the story actually made a physical, written version.

The later history of the story is fascinating, as it became a chapbook in Spain, which remained in print (in various editions) up to the early 20th century. Cervantes mentions it as one of the inspirations for Don Quixote’s quest. By this point the top billing of the title mentions the villain, Tablante de Ricamonte (in the medieval version: Taulat de Rogimon), and Jaufre takes second place. It turns up as a metrical romance in the Philippines, which suggests that the Spanish carried the story with them. In France, it became slightly confused with another romance, Le Bel Inconnu, and then retold in a 19th century adaptation by Jean-Bernard Marie-Lafon, Le Chevalier Jaufre et la Belle Brunissende. This then was translated into English in 1856 by Alfred Elwes as Jaufre the Knight and the Fair Brunissend, and then in the 1930s the American author Vernon Ives produced another retelling, Jaufre the Knight and the Fair Brunissend. All of these adaptations have some quaint errors and were clearly designed for the audience of their time. There are some more academic translations available, into English, Spanish and Italian. Another fascinating survival of the story is as a fresco high up on the walls of a room in the Aljaferìa Palace in  Zaragoza. Only a couple of panels remain, but again, they demonstrate the popularity of the story.

Zaragoza. Only a couple of panels remain, but again, they demonstrate the popularity of the story.

I first read Jaufre as an undergraduate, as part of the work I was doing on the troubadours at Warwick University, under the tuition of Dr Linda Paterson. She knew of my interest in all things Arthurian, and left me free to explore it and draw my own conclusions. I loved it from the start. There is something about the authorial voice which distinguishes it from other medieval romances, and some distinct quirkiness about some of the episodes, and there are some superbly feisty women, too. I stayed on at Warwick to complete an MA, and wrote a dissertation about it, as I was fascinated at the time with the folklore motifs. I went back to it a few years later, by now working full-time as a civil servant in London, picking up some of the threads to do a part-time MPhil at Birkbeck College, but before getting too far into that I was offered the chance to live and teach in France, at the Université Lyon II in Lyon. Once there I was distracted by teaching and my wonderful teaching colleagues. I tried again to work on an MPhil part-time once I was back in London and teaching, but this time the distraction came in the form of music and touring. Finally a few years ago I retired from the day job, and found a home for my research with Cardiff University (School of Welsh, although Jaufre has no real connection with Wales or Welsh), working with Sioned Davies, who has written on medieval storytelling, with Carlos Sanz Mingo, who is an Arthurian scholar and knows Occitan, and with some consultations with Juliette Wood, who knows folklore. I completed my PhD in 2019.

This time, however, I was concentrating on the storytelling aspects of Jaufre, as my performing career has been full of songs and stories, and I had become convinced that telling the story to audiences would be entertaining for audiences and help to resolve some of the questions I had about some of the episodes. It turned out to do both of those things.

So – rather than re-write my thesis for you now, I’ll just put a few conclusions on here.

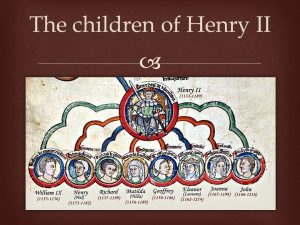

First of all, by asking the question “Why was a story about King Arthur written for a king of Aragon?” and investigating the history of the  various kings suggested, I discovered that James 1 of Aragon was married first to Leonor (who is almost forgotten by most accounts of his reign), and Leonor was a grand-daughter of Alienor of Aquitaine and Henry II of England. This is significant, because Alienor’s extended family were largely responsible for the promotion and dissemination of the Arthurian tales throughout Europe. There are also a number of other features of Jaufre which could be seen as references to Leonor’s family. If it was written at this point in James’ reign, he would have been in his teens, and the story is, as you will hear, perfect for a boy of that age, particularly one who had a strong moral sense and who felt he had been preserved by God to do God’s work. (Yes, I can tell that story, too – at a later date). In the year 1225, James would have been 17, and was raising an army to lay siege to the Muslim stronghold of Peñiscola in southern Spain. When the siege did take place, it was something of a disaster – so my theory is that Jaufre was written in the early part of the year, as there are references only to great victories by the king.

various kings suggested, I discovered that James 1 of Aragon was married first to Leonor (who is almost forgotten by most accounts of his reign), and Leonor was a grand-daughter of Alienor of Aquitaine and Henry II of England. This is significant, because Alienor’s extended family were largely responsible for the promotion and dissemination of the Arthurian tales throughout Europe. There are also a number of other features of Jaufre which could be seen as references to Leonor’s family. If it was written at this point in James’ reign, he would have been in his teens, and the story is, as you will hear, perfect for a boy of that age, particularly one who had a strong moral sense and who felt he had been preserved by God to do God’s work. (Yes, I can tell that story, too – at a later date). In the year 1225, James would have been 17, and was raising an army to lay siege to the Muslim stronghold of Peñiscola in southern Spain. When the siege did take place, it was something of a disaster – so my theory is that Jaufre was written in the early part of the year, as there are references only to great victories by the king.

I also discovered that there was more humour in the story than I had expected, which became apparent when it was told to an audience. I hope my re-telling will make you smile in places, too.

Finally, because a number of people have asked me, I decided to write my own adaptation of the story, so that those who have heard part of the tale can hear the full thing. (I would, by the way, love to hear from a publisher to get a print version out there!) It’s an adaptation rather than a translation as I have deliberately omitted some of the lengthy prayers, interior monologues about love, religious invocations and praise for the king of Aragon, but I have attempted to use a similar tone and include some of my favourite turns of phrase from the original. The original is written in rhyming couplets – this is somewhat tricksy to maintain in modern English, so I have put some passages into rhyme, especially when they are repeating a motif from the story.

I have been lucky to meet David Yardley on line, and he has been a willing collaborator with creating the signature music for this podcast.

I hope you enjoy it!

Paypal.me/AnneListerGB